Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Passport Photographs

Braceros

This man was one of the many guest workers who came to the U. S. within the framework of the Bracero Program. He was photographed for his passport. "Bracero" was a guest worker program between Mexico and the United States between 1942 and 1964 (“bracero” means manual laborer). It was initiated during World War II, due to the increasing demand in manual labor. It grew out of a series of bi-lateral agreements between the two states that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States to work on, short-term, primarily agricultural labor contracts. During those 22 years, 4.6 million contracts were signed, with many individuals returning several times on different contracts, making it the largest U.S. contract labor program. Most of the braceros were skilled farm laborers. During the first five years of the program, Texas farmers chose not to participate in the restrictive accord. However, approximately 300,000 Mexican workers came to the U.S. annually. This abundant supply of labor finally enticed Texans to participate fully in the program. By the end of the 1950s, Texas was receiving large numbers of braceros. In the El Paso region, as in many regions, the Bracero program contributed significantly to the growth of the agricultural economy. Huge numbers of candidates arrived by train to the northern border. Ciudad Juárez became a substantial gathering point for the agricultural labor force. In El Paso, for example, Rio Vista was a farm that was transformed into an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) reception center where the processing of braceros took place. They had to undergo testing and medical examinations there. More than 80.000 braceros crossed through El Paso annually. Some of them never returned but stayed in the U.S. and were able to establish permanent residency or citizenship. Some stayed illegally after the expiration of their contract. The program was very controversial: In theory, the program protected the workers in regard to a minimum wage, adequate shelter, food, sanitation and insurance, but in practice, many of those rules were ignored. Often, Mexican and native workers suffered while growers benefited from plentiful, cheap, labor. Between the 1940s and mid-1950s, farm wages dropped sharply as a percentage of manufacturing wages, a result in part of the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society. In the U.S., they led excluded lives, away from their family, and often experienced harassment, oppression and discrimination. Despite the tremendous difficulties some braceros faced, their jobs in the United States allowed them to help their loved ones during a period of great economic crisis in Mexico. Most workers, however, did not earn nearly as much money in the United States as they had expected. The Bracero Program ended in 1964, due to intense pressure from unions, the mechanization of the agricultural industry, and public awareness of inadequate working and living conditions. In recent years, questions over the payment of wages have become important issues, and have resulted in numerous protests in both Mexico and the United States.

Area: Mission Valley / Socorro

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00002.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

Braceros

These men were two of the many guest workers who came to the U. S. within the framework of the Bracero Program. They were photographed for their passports.

"Bracero" was a guest worker program between Mexico and the United States between 1942 and 1964 (“bracero” means manual laborer). It was initiated during World War II, due to the increasing demand in manual labor. It grew out of a series of bi-lateral agreements between the two states that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States to work on, short-term, primarily agricultural labor contracts. During those 22 years, 4.6 million contracts were signed, with many individuals returning several times on different contracts, making it the largest U.S. contract labor program. Most of the braceros were skilled farm laborers.

During the first five years of the program, Texas farmers chose not to participate in the restrictive accord. However, approximately 300,000 Mexican workers came to the U.S. annually. This abundant supply of labor finally enticed Texans to participate fully in the program. By the end of the 1950s, Texas was receiving large numbers of braceros. In the El Paso region, as in many regions, the Bracero program contributed significantly to the growth of the agricultural economy. Huge numbers of candidates arrived by train to the northern border. Ciudad Juárez became a substantial gathering point for the agricultural labor force. In El Paso, for example, Rio Vista was a farm that was transformed into an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) reception center where the processing of braceros took place. They had to undergo testing and medical examinations there.

More than 80.000 braceros crossed through El Paso annually. Some of them never returned but stayed in the U.S. and were able to establish permanent residency or citizenship. Some stayed illegally after the expiration of their contract.

The program was very controversial: In theory, the program protected the workers in regard to a minimum wage, adequate shelter, food, sanitation and insurance, but in practice, many of those rules were ignored. Often, Mexican and native workers suffered while growers benefited from plentiful, cheap, labor. Between the 1940s and mid-1950s, farm wages dropped sharply as a percentage of manufacturing wages, a result in part of the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society. In the U.S., they led excluded lives, away from their family, and often experienced harassment, oppression and discrimination. Despite the tremendous difficulties some braceros faced, their jobs in the United States allowed them to help their loved ones during a period of great economic crisis in Mexico. Most workers, however, did not earn nearly as much money in the United States as they had expected.

The Bracero Program ended in 1964, due to intense pressure from unions, the mechanization of the agricultural industry, and public awareness of inadequate working and living conditions. In recent years, questions over the payment of wages have become important issues, and have resulted in numerous protests in both Mexico and the United States.

Image Description:Two bracero men look into the camera behind a blank background. The image is of a scanned photograph in black and white. The man on the left wears a button up shirt with a coat with collars made of a different material as his shirt. He has a small mustache but his expression is sullen. There is a second man to his right who wears only a light, possibly muted white colored button up. His facial expression seems optimistic.

Area: Mission Valley / Socorro

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00007.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

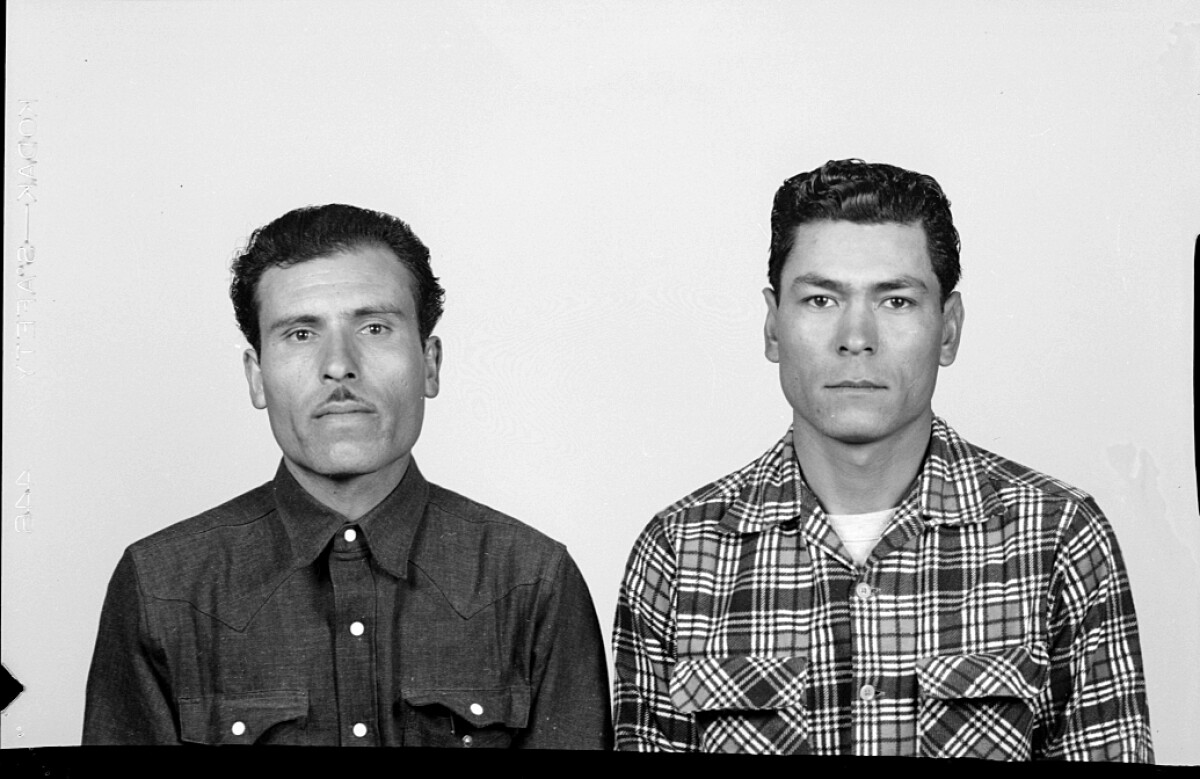

Braceros

These men were two of the many guest workers who came to the U. S. within the framework of the Bracero Program. They were photographed for their passports. "Bracero" was a guest worker program between Mexico and the United States between 1942 and 1964 (“bracero” means manual laborer). It was initiated during World War II, due to the increasing demand in manual labor. It grew out of a series of bi-lateral agreements between the two states that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States to work on, short-term, primarily agricultural labor contracts. During those 22 years, 4.6 million contracts were signed, with many individuals returning several times on different contracts, making it the largest U.S. contract labor program. Most of the braceros were skilled farm laborers. During the first five years of the program, Texas farmers chose not to participate in the restrictive accord. However, approximately 300,000 Mexican workers came to the U.S. annually. This abundant supply of labor finally enticed Texans to participate fully in the program. By the end of the 1950s, Texas was receiving large numbers of braceros. In the El Paso region, as in many regions, the Bracero program contributed significantly to the growth of the agricultural economy. Huge numbers of candidates arrived by train to the northern border. Ciudad Juárez became a substantial gathering point for the agricultural labor force. In El Paso, for example, Rio Vista was a farm that was transformed into an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) reception center where the processing of braceros took place. They had to undergo testing and medical examinations there. More than 80.000 braceros crossed through El Paso annually. Some of them never returned but stayed in the U.S. and were able to establish permanent residency or citizenship. Some stayed illegally after the expiration of their contract. The program was very controversial: In theory, the program protected the workers in regard to a minimum wage, adequate shelter, food, sanitation and insurance, but in practice, many of those rules were ignored. Often, Mexican and native workers suffered while growers benefited from plentiful, cheap, labor. Between the 1940s and mid-1950s, farm wages dropped sharply as a percentage of manufacturing wages, a result in part of the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society. In the U.S., they led excluded lives, away from their family, and often experienced harassment, oppression and discrimination. Despite the tremendous difficulties some braceros faced, their jobs in the United States allowed them to help their loved ones during a period of great economic crisis in Mexico. Most workers, however, did not earn nearly as much money in the United States as they had expected. The Bracero Program ended in 1964, due to intense pressure from unions, the mechanization of the agricultural industry, and public awareness of inadequate working and living conditions. In recent years, questions over the payment of wages have become important issues, and have resulted in numerous protests in both Mexico and the United States.

Area: Mission Valley / Socorro

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00012.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

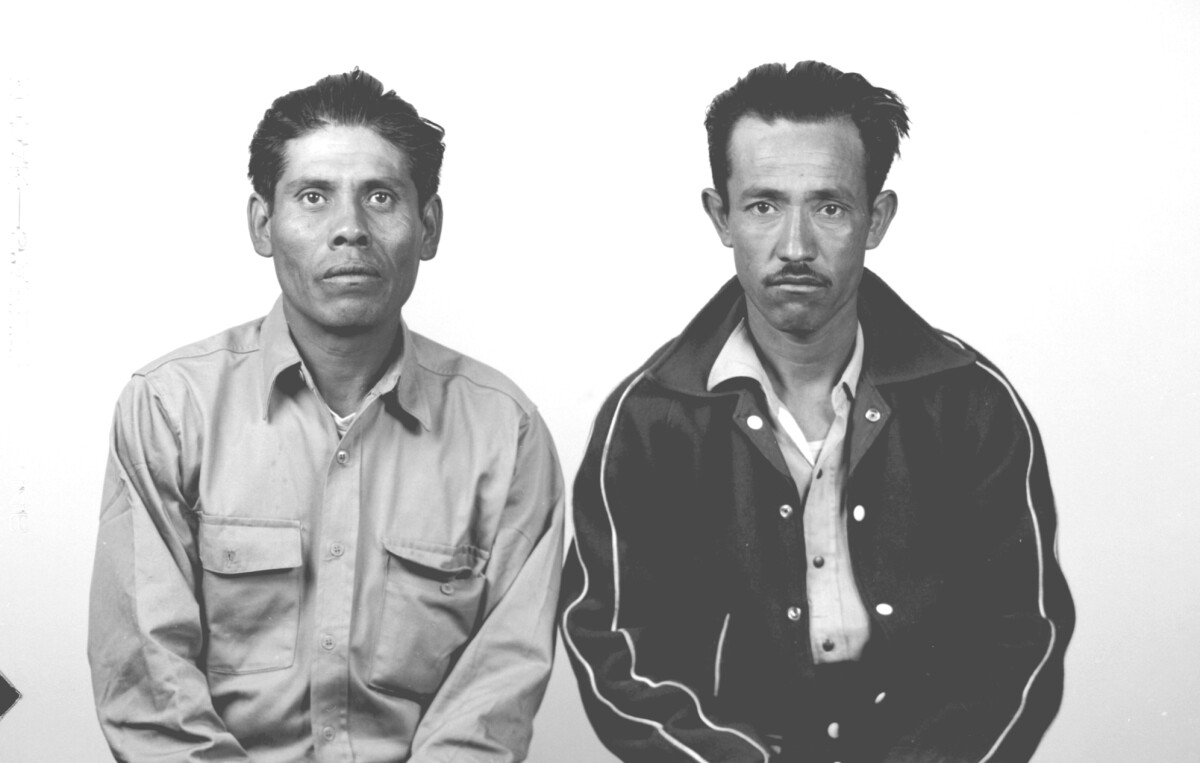

Braceros

These men were two of the many guest workers who came to the U. S. within the framework of the Bracero Program. They were photographed for their passports.

"Bracero" was a guest worker program between Mexico and the United States between 1942 and 1964 (“bracero” means manual laborer). It was initiated during World War II, due to the increasing demand in manual labor. It grew out of a series of bi-lateral agreements between the two states that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States to work on, short-term, primarily agricultural labor contracts. During those 22 years, 4.6 million contracts were signed, with many individuals returning several times on different contracts, making it the largest U.S. contract labor program. Most of the braceros were skilled farm laborers.

During the first five years of the program, Texas farmers chose not to participate in the restrictive accord. However, approximately 300,000 Mexican workers came to the U.S. annually. This abundant supply of labor finally enticed Texans to participate fully in the program. By the end of the 1950s, Texas was receiving large numbers of braceros. In the El Paso region, as in many regions, the Bracero program contributed significantly to the growth of the agricultural economy. Huge numbers of candidates arrived by train to the northern border. Ciudad Juárez became a substantial gathering point for the agricultural labor force. In El Paso, for example, Rio Vista was a farm that was transformed into an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) reception center where the processing of braceros took place. They had to undergo testing and medical examinations there.

More than 80.000 braceros crossed through El Paso annually. Some of them never returned but stayed in the U.S. and were able to establish permanent residency or citizenship. Some stayed illegally after the expiration of their contract.

The program was very controversial: In theory, the program protected the workers in regard to a minimum wage, adequate shelter, food, sanitation and insurance, but in practice, many of those rules were ignored. Often, Mexican and native workers suffered while growers benefited from plentiful, cheap, labor. Between the 1940s and mid-1950s, farm wages dropped sharply as a percentage of manufacturing wages, a result in part of the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society. In the U.S., they led excluded lives, away from their family, and often experienced harassment, oppression and discrimination. Despite the tremendous difficulties some braceros faced, their jobs in the United States allowed them to help their loved ones during a period of great economic crisis in Mexico. Most workers, however, did not earn nearly as much money in the United States as they had expected.

The Bracero Program ended in 1964, due to intense pressure from unions, the mechanization of the agricultural industry, and public awareness of inadequate working and living conditions. In recent years, questions over the payment of wages have become important issues, and have resulted in numerous protests in both Mexico and the United States.

Image Description:An image in black and white of two bracero men sitting side by side. The man to the left wears a jumper sweater over a pointed and collared button-up. The man to his right wears a pointed collar shirt and a leather jacket. His hair is long and styled upwards

Area: Mission Valley / Socorro

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00011.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

Braceros

These men were two of the many guest workers who came to the U. S. within the framework of the Bracero Program. They were photographed for their passports. "Bracero" was a guest worker program between Mexico and the United States between 1942 and 1964 (“bracero” means manual laborer). It was initiated during World War II, due to the increasing demand in manual labor. It grew out of a series of bi-lateral agreements between the two states that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States to work on, short-term, primarily agricultural labor contracts. During those 22 years, 4.6 million contracts were signed, with many individuals returning several times on different contracts, making it the largest U.S. contract labor program. Most of the braceros were skilled farm laborers. During the first five years of the program, Texas farmers chose not to participate in the restrictive accord. However, approximately 300,000 Mexican workers came to the U.S. annually. This abundant supply of labor finally enticed Texans to participate fully in the program. By the end of the 1950s, Texas was receiving large numbers of braceros. In the El Paso region, as in many regions, the Bracero program contributed significantly to the growth of the agricultural economy. Huge numbers of candidates arrived by train to the northern border. Ciudad Juárez became a substantial gathering point for the agricultural labor force. In El Paso, for example, Rio Vista was a farm that was transformed into an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) reception center where the processing of braceros took place. They had to undergo testing and medical examinations there. More than 80.000 braceros crossed through El Paso annually. Some of them never returned but stayed in the U.S. and were able to establish permanent residency or citizenship. Some stayed illegally after the expiration of their contract. The program was very controversial: In theory, the program protected the workers in regard to a minimum wage, adequate shelter, food, sanitation and insurance, but in practice, many of those rules were ignored. Often, Mexican and native workers suffered while growers benefited from plentiful, cheap, labor. Between the 1940s and mid-1950s, farm wages dropped sharply as a percentage of manufacturing wages, a result in part of the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society. In the U.S., they led excluded lives, away from their family, and often experienced harassment, oppression and discrimination. Despite the tremendous difficulties some braceros faced, their jobs in the United States allowed them to help their loved ones during a period of great economic crisis in Mexico. Most workers, however, did not earn nearly as much money in the United States as they had expected. The Bracero Program ended in 1964, due to intense pressure from unions, the mechanization of the agricultural industry, and public awareness of inadequate working and living conditions. In recent years, questions over the payment of wages have become important issues, and have resulted in numerous protests in both Mexico and the United States.

Area: Mission Valley / Socorro

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00006.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

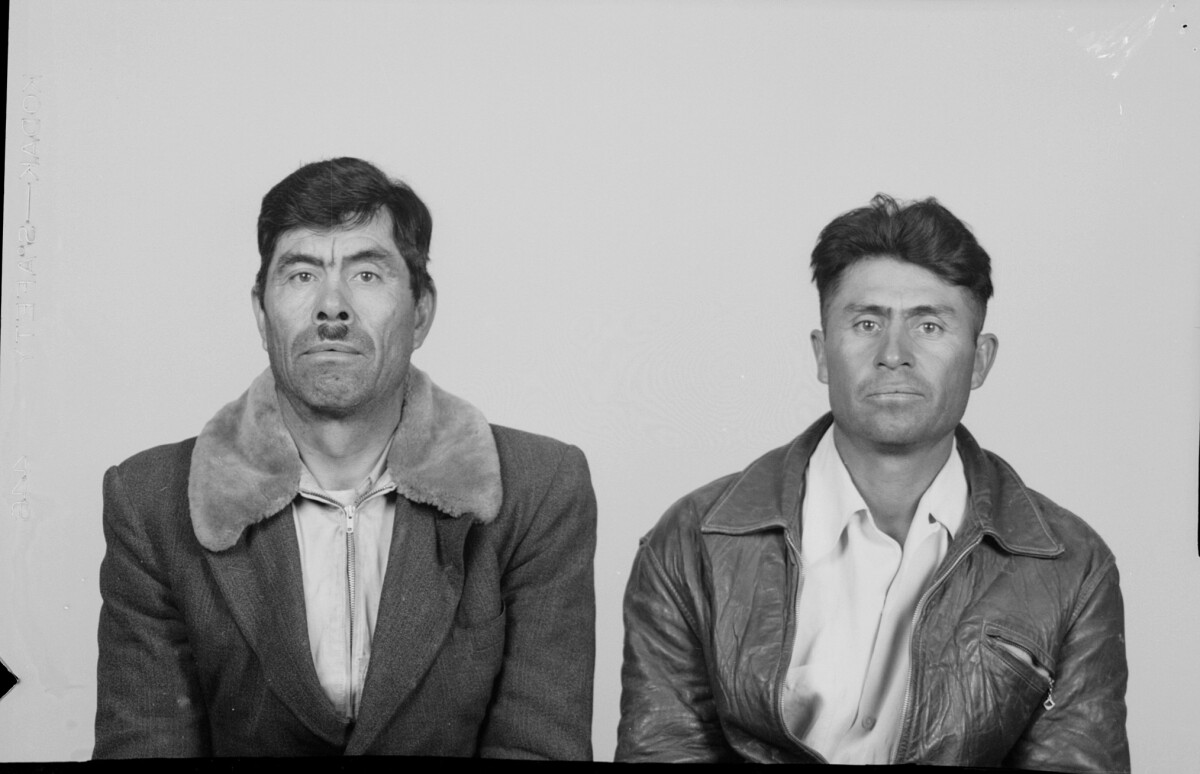

Bracero

This man was one of the many guest workers who came to the U. S. within the framework of the Bracero Program. He was photographed for his passport.

"Bracero" was a guest worker program between Mexico and the United States between 1942 and 1964 (“bracero” means manual laborer). It was initiated during World War II, due to the increasing demand in manual labor. It grew out of a series of bi-lateral agreements between the two states that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States to work on, short-term, primarily agricultural labor contracts. During those 22 years, 4.6 million contracts were signed, with many individuals returning several times on different contracts, making it the largest U.S. contract labor program. Most of the braceros were skilled farm laborers.

During the first five years of the program, Texas farmers chose not to participate in the restrictive accord. However, approximately 300,000 Mexican workers came to the U.S. annually. This abundant supply of labor finally enticed Texans to participate fully in the program. By the end of the 1950s, Texas was receiving large numbers of braceros. In the El Paso region, as in many regions, the Bracero program contributed significantly to the growth of the agricultural economy. Huge numbers of candidates arrived by train to the northern border. Ciudad Juárez became a substantial gathering point for the agricultural labor force. In El Paso, for example, Rio Vista was a farm that was transformed into an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) reception center where the processing of braceros took place. They had to undergo testing and medical examinations there.

More than 80.000 braceros crossed through El Paso annually. Some of them never returned but stayed in the U.S. and were able to establish permanent residency or citizenship. Some stayed illegally after the expiration of their contract.

The program was very controversial: In theory, the program protected the workers in regard to a minimum wage, adequate shelter, food, sanitation and insurance, but in practice, many of those rules were ignored. Often, Mexican and native workers suffered while growers benefited from plentiful, cheap, labor. Between the 1940s and mid-1950s, farm wages dropped sharply as a percentage of manufacturing wages, a result in part of the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society. In the U.S., they led excluded lives, away from their family, and often experienced harassment, oppression and discrimination. Despite the tremendous difficulties some braceros faced, their jobs in the United States allowed them to help their loved ones during a period of great economic crisis in Mexico. Most workers, however, did not earn nearly as much money in the United States as they had expected.

The Bracero Program ended in 1964, due to intense pressure from unions, the mechanization of the agricultural industry, and public awareness of inadequate working and living conditions. In recent years, questions over the payment of wages have become important issues, and have resulted in numerous protests in both Mexico and the United States.

Image Description: : A scanned photograph in black and white of a bracero man behind a blank background. He seems to be around his mid 30’s. He looks directly into the camera with a gentle smile. He is wearing a button up shirt with two pockets that have two buttons on them and jeans. He sits with his hands on his legs. There is a tattoo on his right forearm.

Area: Mission Valley / Socorro

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00015.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

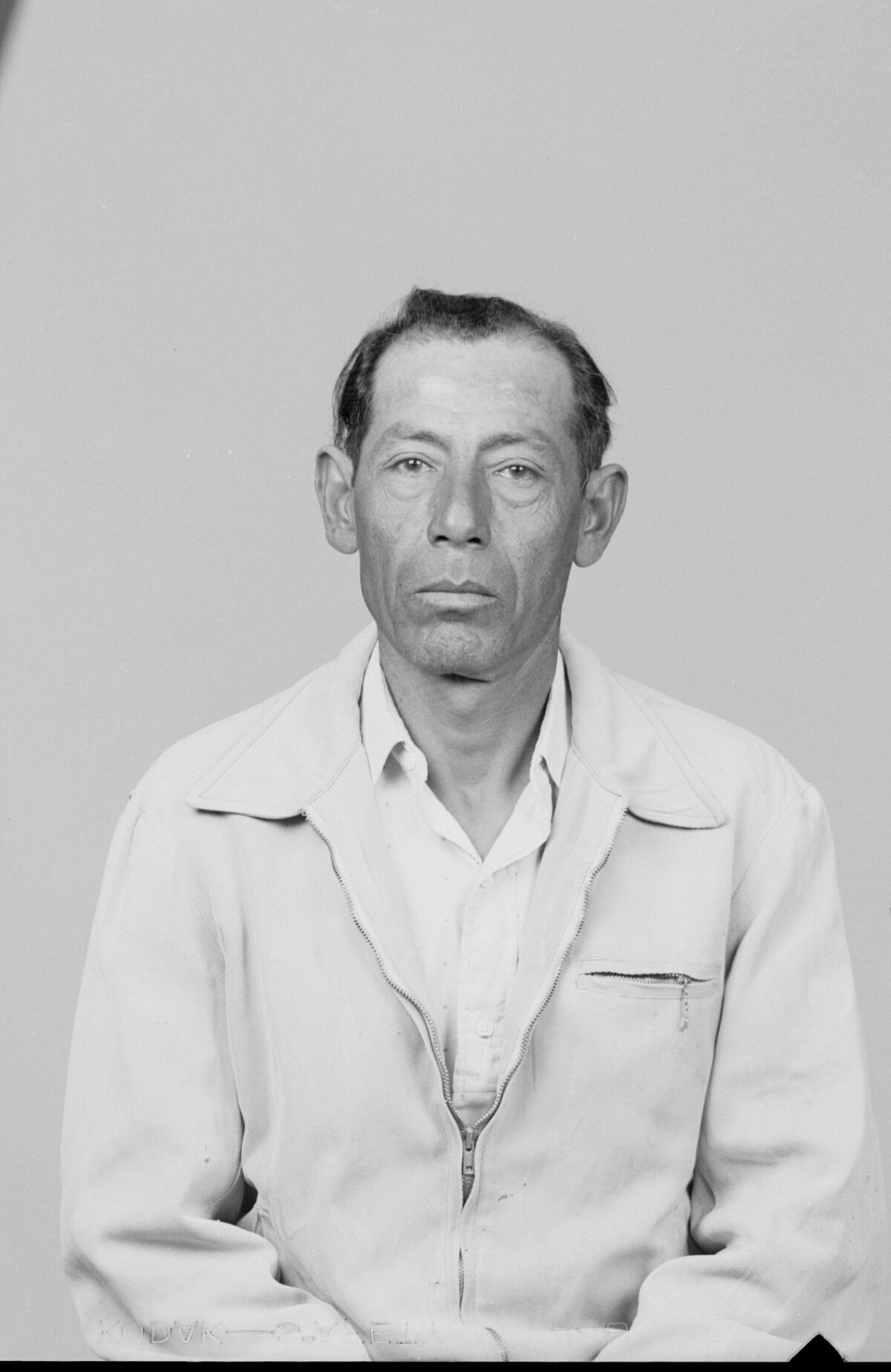

Bracero

This man was one of the many guest workers who came to the U. S. within the framework of the Bracero Program. He was photographed for his passport.

"Bracero" was a guest worker program between Mexico and the United States between 1942 and 1964 (“bracero” means manual laborer). It was initiated during World War II, due to the increasing demand in manual labor. It grew out of a series of bi-lateral agreements between the two states that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States to work on, short-term, primarily agricultural labor contracts. During those 22 years, 4.6 million contracts were signed, with many individuals returning several times on different contracts, making it the largest U.S. contract labor program. Most of the braceros were skilled farm laborers.

During the first five years of the program, Texas farmers chose not to participate in the restrictive accord. However, approximately 300,000 Mexican workers came to the U.S. annually. This abundant supply of labor finally enticed Texans to participate fully in the program. By the end of the 1950s, Texas was receiving large numbers of braceros. In the El Paso region, as in many regions, the Bracero program contributed significantly to the growth of the agricultural economy. Huge numbers of candidates arrived by train to the northern border. Ciudad Juárez became a substantial gathering point for the agricultural labor force. In El Paso, for example, Rio Vista was a farm that was transformed into an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) reception center where the processing of braceros took place. They had to undergo testing and medical examinations there.

More than 80.000 braceros crossed through El Paso annually. Some of them never returned but stayed in the U.S. and were able to establish permanent residency or citizenship. Some stayed illegally after the expiration of their contract.

The program was very controversial: In theory, the program protected the workers in regard to a minimum wage, adequate shelter, food, sanitation and insurance, but in practice, many of those rules were ignored. Often, Mexican and native workers suffered while growers benefited from plentiful, cheap, labor. Between the 1940s and mid-1950s, farm wages dropped sharply as a percentage of manufacturing wages, a result in part of the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society. In the U.S., they led excluded lives, away from their family, and often experienced harassment, oppression and discrimination. Despite the tremendous difficulties some braceros faced, their jobs in the United States allowed them to help their loved ones during a period of great economic crisis in Mexico. Most workers, however, did not earn nearly as much money in the United States as they had expected.

The Bracero Program ended in 1964, due to intense pressure from unions, the mechanization of the agricultural industry, and public awareness of inadequate working and living conditions. In recent years, questions over the payment of wages have become important issues, and have resulted in numerous protests in both Mexico and the United States.

Image Description: : A scanned photograph in black and white of a bracero man behind a blank background. He seems to be approximately around his late 40’s or early 50’s. He looks directly into the camera with a serious expression. The man is wearing a button up shirt and a jacket with a collar. His hands are folded into his lap.

Area: Mission Valley / Socorro

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00021.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

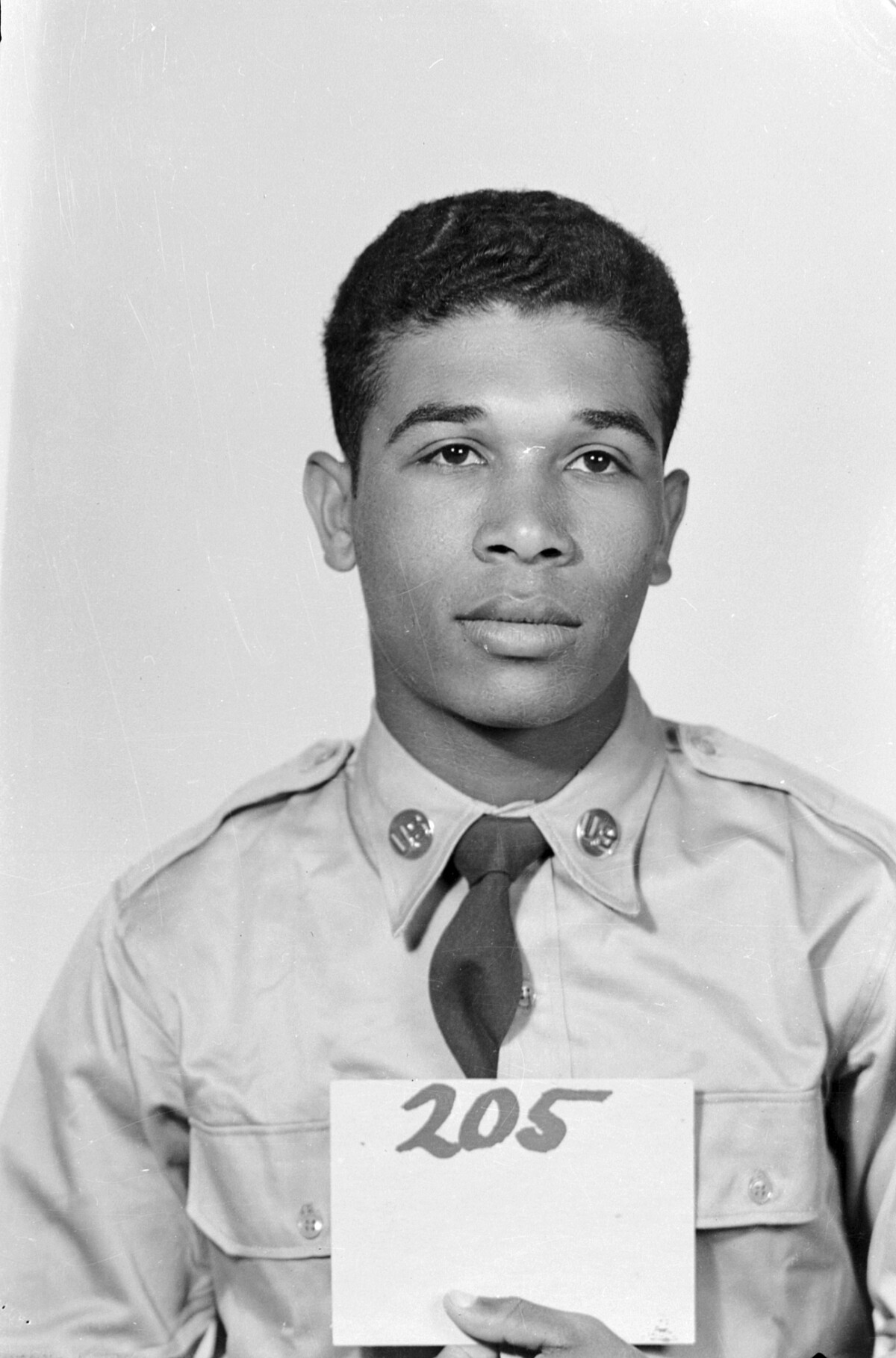

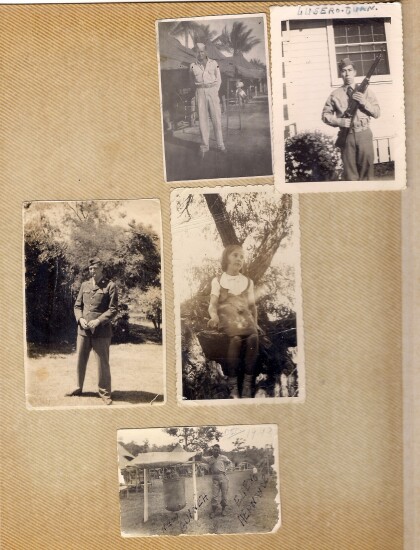

Passport Photograph

The image was taken by the Casaola Photograph Studio. It is a passport picture, taken of an unknown person.

Area: Central / Downtown

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00024.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

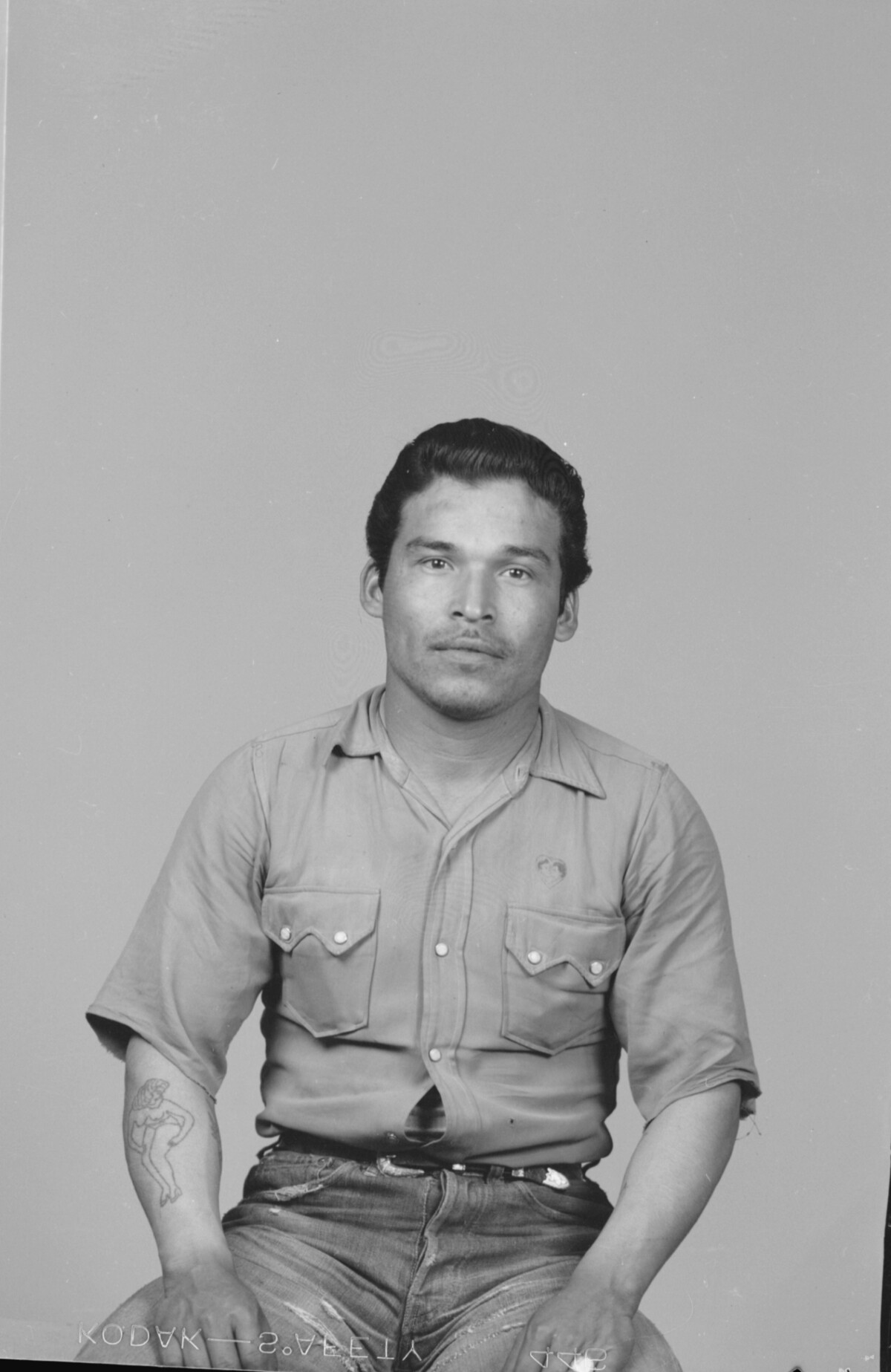

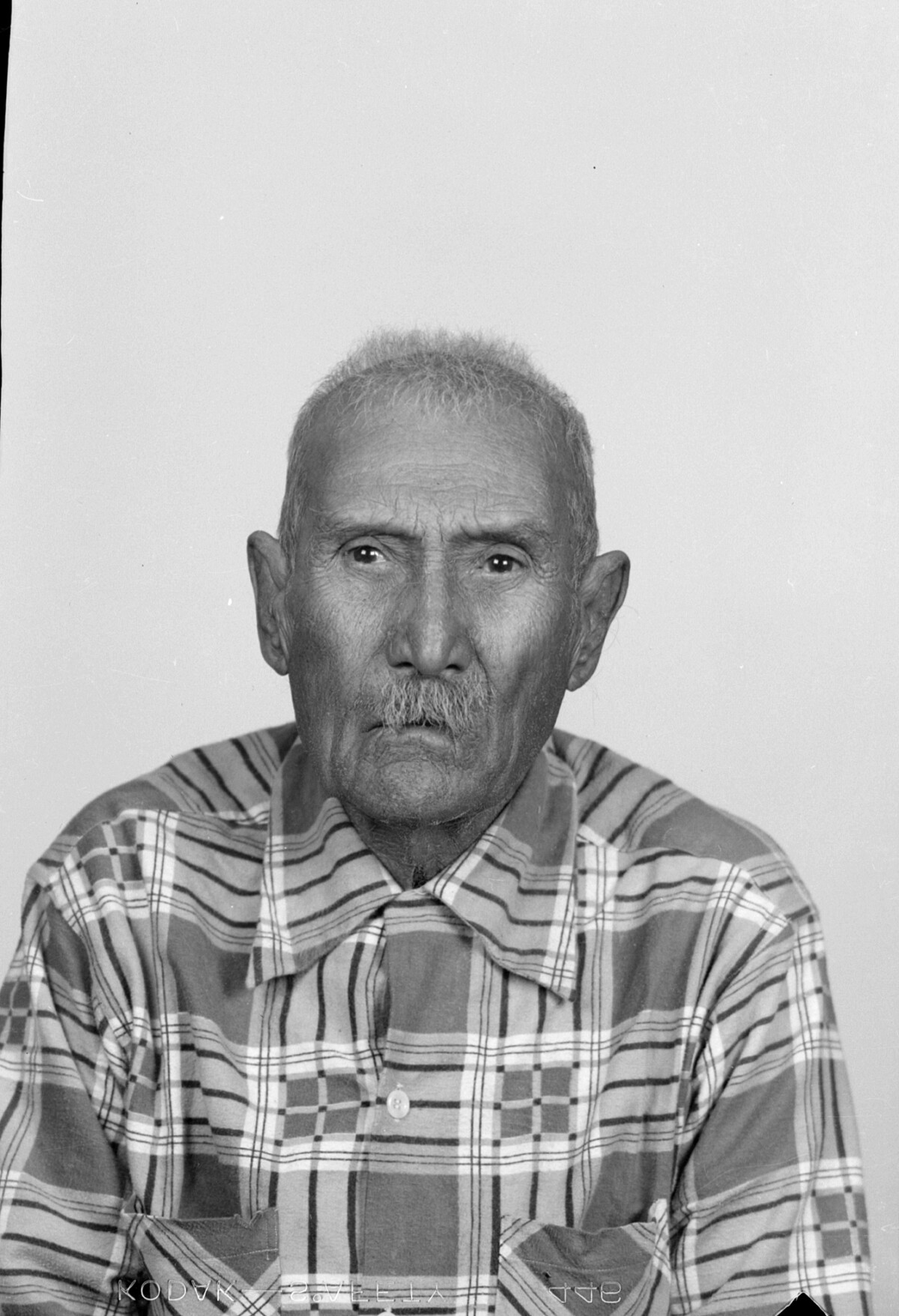

Bracero

This man was one of the many guest workers who came to the U. S. within the framework of the Bracero Program. He was photographed for his passport.

"Bracero" was a guest worker program between Mexico and the United States between 1942 and 1964 (“bracero” means manual laborer). It was initiated during World War II, due to the increasing demand in manual labor. It grew out of a series of bi-lateral agreements between the two states that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States to work on, short-term, primarily agricultural labor contracts. During those 22 years, 4.6 million contracts were signed, with many individuals returning several times on different contracts, making it the largest U.S. contract labor program. Most of the braceros were skilled farm laborers.

During the first five years of the program, Texas farmers chose not to participate in the restrictive accord. However, approximately 300,000 Mexican workers came to the U.S. annually. This abundant supply of labor finally enticed Texans to participate fully in the program. By the end of the 1950s, Texas was receiving large numbers of braceros. In the El Paso region, as in many regions, the Bracero program contributed significantly to the growth of the agricultural economy. Huge numbers of candidates arrived by train to the northern border. Ciudad Juárez became a substantial gathering point for the agricultural labor force. In El Paso, for example, Rio Vista was a farm that was transformed into an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) reception center where the processing of braceros took place. They had to undergo testing and medical examinations there.

More than 80.000 braceros crossed through El Paso annually. Some of them never returned but stayed in the U.S. and were able to establish permanent residency or citizenship. Some stayed illegally after the expiration of their contract.

The program was very controversial: In theory, the program protected the workers in regard to a minimum wage, adequate shelter, food, sanitation and insurance, but in practice, many of those rules were ignored. Often, Mexican and native workers suffered while growers benefited from plentiful, cheap, labor. Between the 1940s and mid-1950s, farm wages dropped sharply as a percentage of manufacturing wages, a result in part of the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society. In the U.S., they led excluded lives, away from their family, and often experienced harassment, oppression and discrimination. Despite the tremendous difficulties some braceros faced, their jobs in the United States allowed them to help their loved ones during a period of great economic crisis in Mexico. Most workers, however, did not earn nearly as much money in the United States as they had expected.

The Bracero Program ended in 1964, due to intense pressure from unions, the mechanization of the agricultural industry, and public awareness of inadequate working and living conditions. In recent years, questions over the payment of wages have become important issues, and have resulted in numerous protests in both Mexico and the United States.

Image Description: A scanned photograph in black and white of a bracero man behind a blank background. He seems to be around his mid 30’s. He looks directly into the camera. He is wearing a flannel shirt, with his hands confidently on his hips.

Area: Mission Valley / Socorro

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00023.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

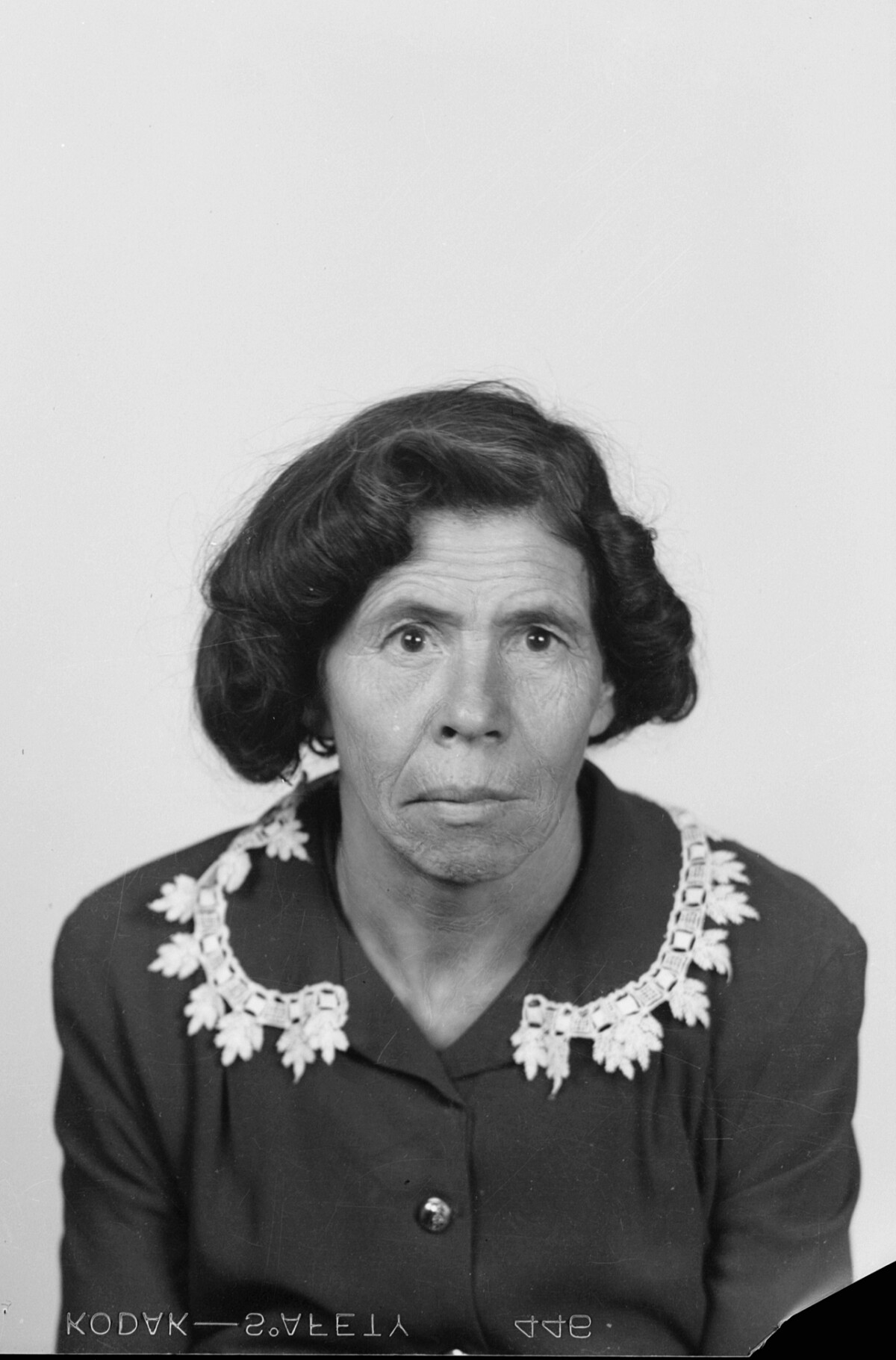

Passport Photograph

The image was taken by the Casaola Photograph Studio. It is a passport picture, taken of an unknown person.

Area: Central / Downtown

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00027.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

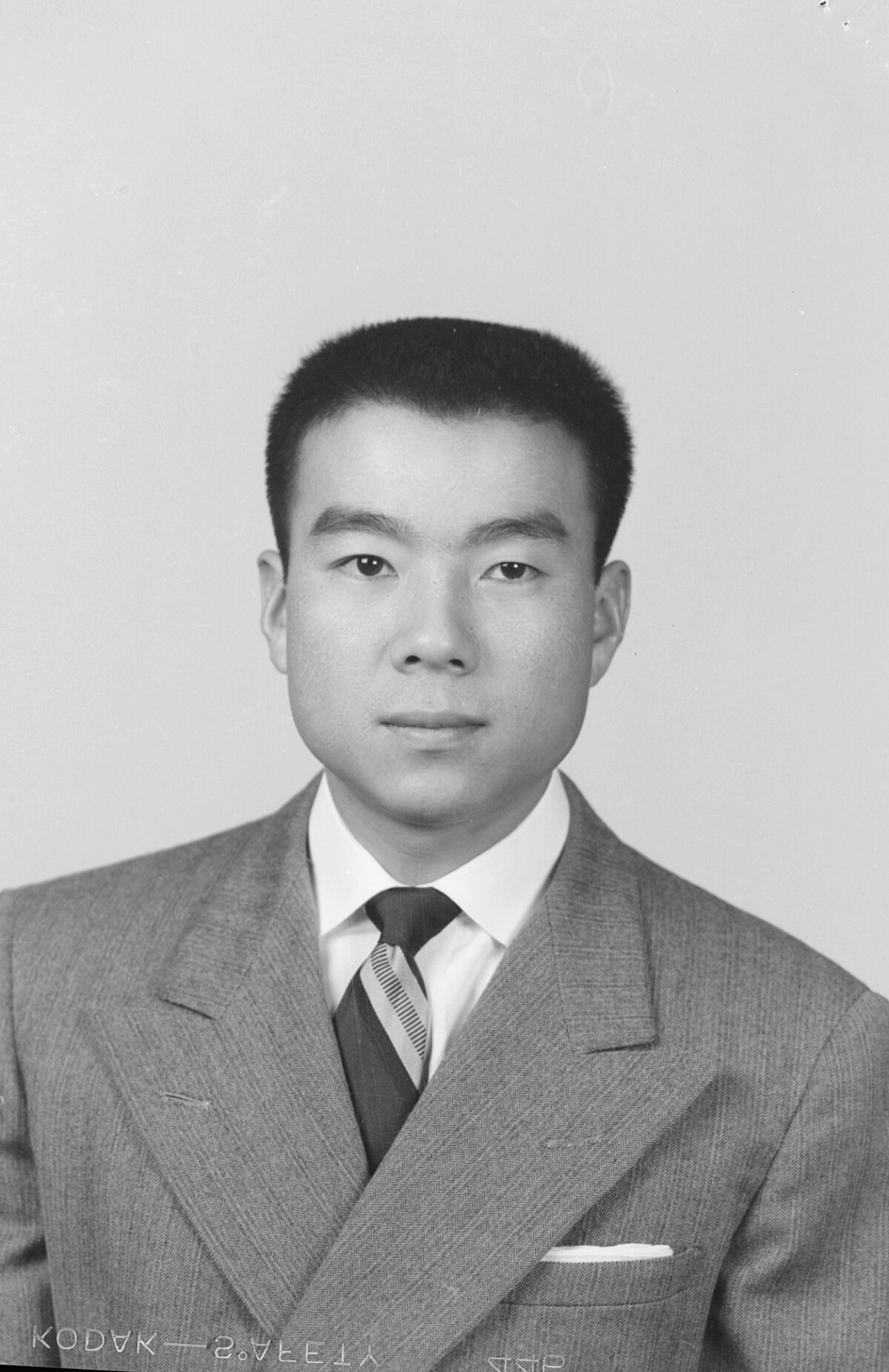

Passport Photograph

The image was taken by the Casaola Photograph Studio. It is a passport picture, taken of an unknown person.

Area: Central / Downtown

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00040.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

Passport Photograph

The image was taken by the Casaola Photograph Studio. It is a passport picture, taken of an unknown person.

Area: Central / Downtown

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00046.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

Passport Photograph

The image was taken by the Casaola Photograph Studio. It is a passport picture, taken of an unknown person.

Area: Central / Downtown

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00035.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

Passport Photograph

The image was taken by the Casaola Photograph Studio. It is a passport picture, taken of an unknown person.

Area: Central / Downtown

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00070.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

Passport Photograph

The image was taken by the Casaola Photograph Studio. It is a passport picture, taken of an unknown person.

Area: Central / Downtown

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00069.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

Passport Photograph

The image was taken by the Casaola Photograph Studio. It is a passport picture, taken of an unknown person.

Area: Central / Downtown

Source: C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections, University of Texas at El Paso Library. Collection Name: Casasola Photograph Collection. Photo ID: PH041-09-00080.

Uploaded by: UTEP Library Special Collections

Report this entry

More from the same community-collection

Roberto R. Bustamante Wastewater Treatment Plant

The Roberto R. Bustamante Wastewater Treatment Plant began ...

EPCC Mission del Paso Campus Completed

The Mission del Paso campus opened, creating five conveniently ...

EPCC Professional Truck Driving Facility Opened

The Professional Truck Driving Facility opened at the Mission ...

EPCC Law Enforcement Training Academy and Facility Opened

$2.7 million Law Enforcement Training Academy and Facility ...

EPCC Law Enforcement Training Academy and Facility Opened

$2.7 million Law Enforcement Training Academy and Facility ...

EPCC Mission Early College High School Opened

In late August, EPCC opened Mission Early College High School ...

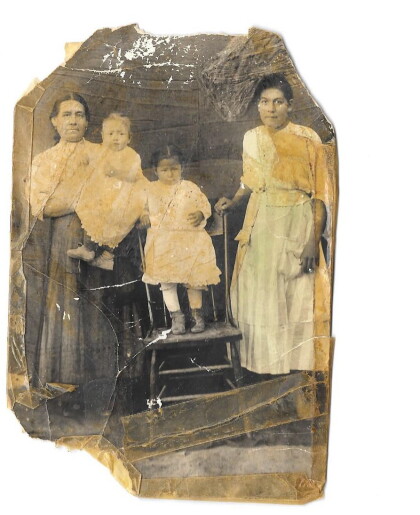

Marcelina Marquez Fernandez and Family

My maternal great-grandmother, Marcelina Marquez Fernandez ...

A Page from my paternal Grand-father, Ramon Fernandez

A page from my paternal Grand-father, Ramon Fernandez relating ...

The Fernandez Family of Socorro, Texas

Mercedes Fernandez, My grandfather Ramon sister. Here she is ...

The Fernandez Family of Socorro, Texas

My Grandfather, Ramon Fernandez sister, Lucia Fernandez Vasquez.

The Fernandez Family of Socorro, Texas

My Grandfather, Ramon Fernandez older sister, Amparo Fernandez ...

The Fernandez Family of Socorro, Texas

My Grandfather, Ramon Fernandez sisters and their friends ...

Alumnae and students, Loretto Academy

Eva Ross with students and alumnae of Loretto Academy Dec 5 2022

New Residents in Front of Socorro Mission, 2022

Tawan and Felicia Parsons on the mission trail at the Socorro ...

Comments

Add a comment